Written by: Robert Brennan Hart

I WATCHED MY SON experiment with an AI coding assistant last week, building a functional web application in an afternoon that would have taken me months to construct when I started in the technology industry so many years ago. He moved between the AI’s suggestions and his own logic with the fluency of someone who has never known a world without these tools. The application worked. He learned. He advanced.

Then I received a message from a former colleague – a marketing professional with fifteen years of experience who was laid off nine months ago and hasn’t found a new job since. Her company had given all employees access to AI content tools during her final year there. She’d used them daily, becoming proficient. But now, job searching from home with an aging laptop and unstable internet, she can’t afford subscriptions to the AI platforms that have become industry standard. She watches job postings requiring “demonstrated AI fluency” and knows she’s losing the capability she spent a year developing. The gap between their trajectories isn’t measured in skill or intelligence or effort. It’s measured in continued access to tools that now determine who adapts and who calcifies.

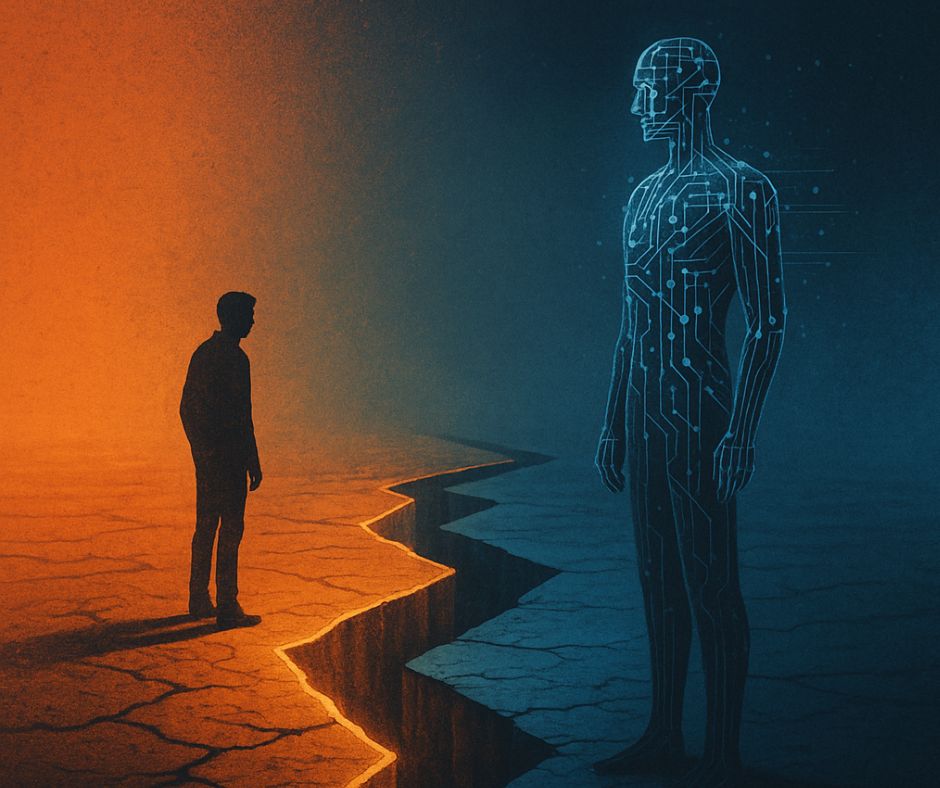

We are witnessing the emergence of a sorting mechanism disguised as meritocracy. AI doesn’t just automate work – it creates a taxonomy of economic value based not on human capability but on continuous access to systems that amplify that capability. And because this sorting happens through technology we’ve been conditioned to view as neutral, we mistake systemic exclusion for individual failure.

THE VELOCITY OF AI transformation creates what appears to be a fair competition: everyone faces the same disruption, the same need to adapt, the same imperative to develop new capabilities. This appearance of equality obscures a brutal reality; the tools required for adaptation are not equally distributed, and crucially, the window for developing fluency is closing faster than most realize.

Here’s what makes this moment distinct from previous technological transitions: AI fluency currently differentiates workers, but soon it will simply qualify them. My son is learning AI tools during the phase when this knowledge still commands premium value. In two years, perhaps less, AI literacy will be table stakes – assumed, required, but no longer particularly valuable. Those gaining fluency now will have accumulated advantages that compound: they’ll understand not just current tools but how to adapt to next-generation systems, which interfaces produce reliable results, which capabilities justify the hype versus which remain theater.

Those locked out now miss this entire developmental arc. They’ll eventually encounter AI tools, probably through some mandated workplace training, but they’ll be learning table stakes after the differentiation window has closed. They’ll be perpetually behind, trying to catch up to a baseline that keeps rising while others who started earlier continue advancing.

Recent employment data makes the sorting visible for those willing to look. A study of software developers found that those with regular access to AI coding assistants averaged forty-three percent higher productivity and commanded salaries approximately thirty-five percent above their non-AI-enhanced peers. Graphic designers fluent in AI image generation tools report similar wage premiums. Content strategists who can leverage large language models efficiently face substantially higher demand than those working without AI augmentation.

But here’s what the data doesn’t show; how many workers never appear in these statistics because they can’t access the tools required to compete. The person laid off who loses their company-provided AI subscriptions. The freelancer who can’t afford monthly platform fees that now total several hundred dollars. The job seeker with unreliable connectivity who can’t complete the “AI proficiency assessments” that increasingly gate employment. They simply disappear from labor markets that have reorganized around capabilities they cannot demonstrate.

CONSIDER WHAT THIS feels like from inside the exclusion. You know AI tools exist. You’ve read articles explaining their importance. Perhaps you’ve even used them briefly, at a library terminal, during a free trial period, through a friend’s account. You understand their value. You recognize your need to develop fluency. But you can’t afford the subscriptions. You can’t risk the connectivity costs of continuous experimentation. You can’t justify the time investment when immediate income generation remains uncertain. So you watch others discuss prompt engineering techniques on social media, share AI-generated work samples, build portfolios that demonstrate capabilities you cannot develop. You feel yourself falling behind in real time, watching the distance grow between where you are and where you need to be, knowing that every day without access makes catching up less probable.

The psychological violence of this awareness – understanding you’re being systematically disadvantaged while being told the tools are “democratically available” – compounds the economic violence. Previous generations facing technological displacement could at least maintain the belief that hard work and determination might overcome barriers. This generation watches algorithms sort them before they’ve had opportunity to demonstrate capability, then gets told their exclusion reflects personal failure rather than infrastructural deprivation.

ORGANIZATIONS DEPLOYING AI SYSTEMS celebrate democratization – anyone can use these tools! But “anyone can use” becomes meaningless when continuous use requires infrastructure that remains profoundly unequally distributed. A free trial teaches you enough to understand what you’re missing but not enough to develop competitive fluency. Occasional access at public terminals lets you glimpse capability without building the muscle memory that comes from daily practice. The tools are “available” in the same way that a gym is available to someone who can only visit for fifteen minutes a month; technically accessible, practically useless.

Meanwhile, those with infrastructure advantages don’t just learn current tools – they develop meta-skills in rapid AI adaptation. They learn how to learn new AI systems quickly, how to evaluate competing platforms efficiently, how to integrate AI capabilities into workflows seamlessly. These meta-skills become even more valuable than specific tool knowledge because they enable continuous adaptation as AI capabilities evolve.

The gap compounds not arithmetically but exponentially. Those with access learn faster because they’ve learned how to learn. Those without access fall further behind not just in current capabilities but in adaptive capacity itself. By the time they gain access; through some future public initiative, through eventual employment, through infrastructure expansion – they’re competing against people who’ve had years to develop fluency and, more critically, years to develop the meta-skills that enable continued advancement.

RECENT JOB POSTINGS reveal the sorting in plain language. “Required: Demonstrated experience with AI tools including ChatGPT, Claude, Midjourney.” “Must show portfolio of AI-enhanced work.” “Seeking candidates with proven track record of AI-augmented productivity gains.” These aren’t requests for general computer literacy or willingness to learn. They’re demands for fluency that requires sustained access to develop.

A graphic designer without reliable internet cannot build an AI-enhanced portfolio. A writer with an aging device cannot demonstrate proficiency with tools that require modern hardware. A data analyst who can’t afford platform subscriptions cannot show a “proven track record” of AI augmentation. The job requirements aren’t technically discriminatory; they don’t mention income, geography, or demographic categories. They simply require capabilities that infrastructure inequality makes impossible for large segments of the population to develop.

This represents a fundamental transformation in how economic stratification operates. Previous barriers at least maintained visibility – explicit discrimination, geographic isolation, educational access gaps. Those barriers could be named, challenged, potentially dismantled. The AI sorting mechanism operates through technology’s apparent neutrality, making the exclusion invisible to those who never encounter it. Those with access see only individual success stories – look how AI democratizes capability! Those without access simply disappear from consideration.

MY SON WILL navigate this transformation during the optimal window. He’s developing AI fluency while it still differentiates, building meta-skills in AI adaptation while the landscape remains relatively stable, establishing patterns of continuous learning while the infrastructure supporting that learning remains accessible to him. By the time AI literacy becomes mere qualification rather than differentiation, he’ll have moved into capabilities that only sustained access could develop.

My former colleague experiences the same transformation from outside the window. She had access, developed initial fluency, then lost it precisely when maintaining that fluency became most critical. She’ll regain access eventually – economics generally prevent permanent total exclusion. But she’ll have missed the differentiation window entirely, entering markets where AI fluency is assumed but no longer particularly valued, competing against those who used the window to develop advantages that now appear insurmountable.

The sorting mechanism makes no judgment about merit. It simply processes inputs – who has access, who develops fluency, who demonstrates capability – and produces outputs in the form of economic stratification that appears to reflect individual achievement. Those sorted favorably receive validation that their success reflects talent and effort. Those sorted unfavorably receive confirmation that their exclusion reflects deficiency. The actual mechanism – infrastructure inequality determining who gets to practice during the crucial window – remains invisible because we’ve been conditioned to view technology access as individual responsibility rather than collective infrastructure.

The particularly urgent dimension here is temporal. We’re not discussing some distant future where AI might matter. We’re in the narrow window when AI fluency still differentiates rather than merely qualifies – when those gaining access now accumulate advantages that will compound across careers, when those locked out now miss developmental opportunities that cannot be recovered later.

Every month hardens the economic divide. The gap expands beyond what individual effort could overcome because it’s not just current knowledge – it’s accumulated practice, developed intuition, established patterns of continuous learning. Those without access during this window won’t just be behind, they’ll be locked into systematic disadvantage in labor markets that have reorganized around capabilities they never had the opportunity to develop.

We stand at a point where intervention might still alter outcomes. Where providing access now might allow those currently excluded to enter the window before it closes entirely. Or we maintain that access remains individual responsibility, watch the sorting operate with perfect efficiency, then congratulate ourselves that the mechanism appeared fair.

My son’s trajectory and my colleague’s trajectory are diverging at this moment. So are millions of others. The question is whether we’ll name this honestly and act accordingly, or whether we’ll maintain comfortable fictions about meritocracy while watching algorithmic sorting create economic stratification that no individual effort can overcome.

The infrastructure to prevent this exists. Organizations like ERA demonstrate that intervention is possible, that functional devices can be diverted from waste streams, refurbished, and placed in the hands of those who need them most. That the window, while closing, has not yet shut. The great sorting is not natural, not inevitable, and not fair. But it is, for this moment, still preventable.